Baillie’s dramas, in particular Plays on the Passions stand

at the crossroads of the Scottish Enlightenment and early Romanticism. One can

see the effect these had on her writing, and may explain her focus on the human

mind and its relationship to human nature. However, her beginnings were with

poetry, for which she was regarded as one of the finest woman poets in her

lifetime. Elizabeth Barrett Browning even hailed her as “the first female poet

in all senses in England.” Her career in poetry sits in contrast with that of

her dramas, for it’s poetry itself which she goes on to criticize in Plays on

the Passions, for they don’t often include human nature in them, creating a

disconnect between the reader and the poem.

Baillie came from an intellectual family with important links

to the major philosophical and scientific communities of the time, in

particular the “common sense” school of philosophy that became known as the

Scottish Enlightenment. Her uncle was William Hunter, anatomist and physician,

who founded the University of Glasgow’s Hunterian Museum, and Matthew, her brother, born in 1761, later

became a medic and anatomist. Baillie, intelligent and with a stimulating

intellectual background, however, was excluded from the scientific world, which

was why she launched her own examination of the psyche.

Edinburgh during the Scottish Enlightenment

Her Plays on the Passions, was produced in

three volumes between 1798 and 1812. The first volume created quite a stir

amongst the literary circles of London and Edinburgh when introduced

anonymously. The speculation into the authorship concluded two years later when

Baillie came forward as the writer of the collection, thereby causing a

subsequent sensation since no one had considered her as a candidate in the

mystery. The three plays which were included were "Count Basil: A

Tragedy," "The Tryal: A

Comedy," which show love from opposing perspectives; and "De Monfort:

A Tragedy," which explores the drama of hate. It’s within Dramas that Baillie believes lies

the most captivating characteristic writing may contain: human nature. Drama is

the purest genre which isn’t caught up in eloquent or flowery rhetoric,

stripping itself from these methodical attributes and bringing it as close to

reality as possible.

So far, we haven’t read any works which would fit completely under

Baillie’s description, for none of them have been Dramatic plays. Nonetheless,

Baillie does recognize that novels may obtain a certain level of real human emotion

which readers can identify themselves with. Baillie states the urge human

beings have of “looking into another man’s closet,” meaning they want to discover

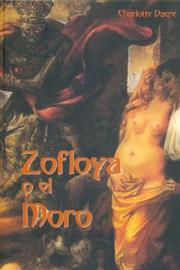

their deepest secrets and motivations for acting the way they do. In Zofloya,

for example, we observe a much more deep evolution within the characters,

especially in Victoria as well as Zofloya, than in A Sicilian Romance, in which

although there are major plot events occurring, the characters show little depth.

Julia’s perfect nature is exactly what Baillie addresses as a lack of human

nature, for it doesn’t depict a realistic human being. However, she also suggests

that just as a perfect depiction of a character is bad, a purely evil on is

too. In Zofloya we can observe this other side of the spectrum, for Zofloya is

depicted as the devil in person. None of these sides contain what Baillie would

see as essential, which is tha of human nature.

Discussion

Questions

1.

Do you agree with Baillie that novels create a disconnect between the reader

and the work itself with the use of rhetoric devices or even the sublime?

2.

Is human nature, as Baillie describes it, in your opinion essential?

3.

What flaws do you think Baillie would see in the novels we’ve read so far?